Photos by John Eder

Researchers have well established nature’s healing powers—its ability to lower blood pressure, reduce anxiety, and boost cognitive function, among many other benefits.

Viewers of Ran Adler’s nature-based art may experience the same positive effects, possibly even then some.

“Calm,” says the artist, surveying Kapnick Hall as he finalizes the exhibition. “That’s what this is all about. Calm.”

There is something uniquely quieting about the new exhibition Internalizing the External: A New Perspective on Nature by Ran Adler—and the artist behind it.

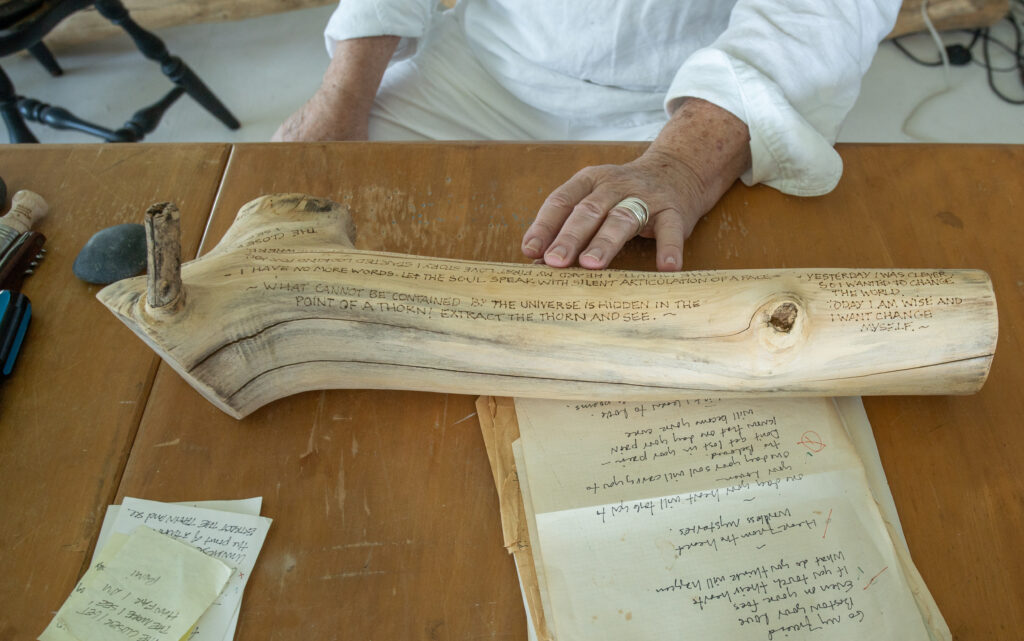

Soul-soothing meditative music greets you when you enter. It is the soundtrack Adler plays while preparing materials at home, a repetitive process he likens to meditation. The seeds, reeds, stalks, and thorns that comprise his works emit a sweet smell, like fresh hay. Oversized pieces hang from the ceiling, allowing viewers to immerse themselves, like wandering a forest. There are stumps on which to sit and read poetry. Adler burned verses from Rumi, the 13th-century Persian poet, into logs salvaged from fallen trees.

And then there is the artist himself, sitting monk-like amid his creations. Adler, 71, sports a shaved head, curling goatee, and tiny round spectacles. On this day—and every day—he’s wearing white, loosely fitting garments. “White is purity,” he explains. “It’s my constant journey to purity, which I never expect to achieve.”

But if you encounter Adler at the exhibition (he has public appearances September 7 and October 19), don’t let his appearance or his Zen-like creations or his philosophical commentary intimidate you. With an impish grin, Adler acknowledges his look is as good for marketing as it is for his soul. “I knew when I moved here, I had to create a brand,” he says. It works. If you see Ran Adler in a room, you instantly want to know more—and he’s happy to indulge you.

I certainly wanted to know more, so shortly before the exhibition opens, I visit Adler at his Naples home where he is immersed in preparations for Internalizing the External.

Adler moved to Naples 20 years ago, bought a modest manufactured home, stripped its dated carpet and dreary panels and painted the entire thing white—floors, walls, ceilings. It’s outfitted with simple wooden furniture, baskets, and wall hangings like a handcrafted piece his sister brought back from Tonga following her Peace Corps service.

“I was searching for a little bit more peace in my life,” he explains. “I went through a real dark period in the ’90s and wanted to find a way to transcend how I am.”

I suspect there’s a book’s worth of adventures in Adler’s biography—his coming of age in the ’60s and ’70s, his nomadic existence (19 cities in three countries), his work in the fashion industry, his stint in Venezuela planning parties for an oil executive, the years when he favored cowboy boots and jeans to linen shirts and fabric shoes.

But I’ll stick to the art.

As a boy growing up in Missouri, Adler liked to gather objects he found outdoors, a precursor of what was to come. Scouting offered more immersion into nature. But his passion for natural materials really emerged in his 30s when he lived in Kansas City by a wholesale flower shop. At night, he’d gather its discarded flowers and make floral arrangements to embellish the dinner parties he and his then-partner liked to throw. Guests loved them. He went on to practice and teach floral design professionally.

Around that time, Adler began studying the work of Andy Goldsworthy, an English sculptor, photographer, and environmentalist known for his site-specific installations.

“He was my major inspiration. He gave me permission, kind of, ‘You can do this, you can take things in nature and manipulate them,’” Adler says. “I learned that it was OK to go in that direction. Other people were doing great things. So, I just started exploring, and that’s how this happened.”

There were other influences along the way: A friend gifted him a volume of poetry by Rumi, now a wellspring of inspiration. “I just liked his whole thing about love being the answer to everything,” Adler says.

A shopkeeper introduced him to Japanese design through her sparse, precise displays. Intrigued, he later traveled to Japan and studied other aspects of that nation’s culture and art. He delved into the writings of Ryokan, a poet, and embraced the concept of “wabi-sabi,” the idea of impermanence and imperfection. Visitors to Kapnick Hall might notice a few pieces that combine natural objects and industrial ones, a Japanese style known as Mono-ha.

By the time he got to Naples, Adler was ready to concentrate solely on his art.

Adler gives natural objects—fallen leaves, discarded seeds, wind-stripped tree thorns—a second life. The pieces on display in Kapnick Hall feature interwoven mahogany pods that flow like a river; silk floss thorns that swoop like birds taking flight; sculptures crafted from reeds, reminiscent of swirling windstorms.

“The joy is watching it change into something else and giving it another life,” Adler says. “The change of color, the change of texture, the change of its story is what I work with.”

Sea grapes are a favorite medium. As they mature, they morph from pea green to bronze and their outer coats disintegrate into a terra cotta-colored dust.

“I call it prayer dust,” Adler says. Repeat guests can watch his sea grape installation transform over the exhibition’s run.

His process begins with foraging. Around Naples, Adler gathers things like mahogany pods and sea grapes, which are so plentiful he packs his home freezer full of them. During a tour of the Garden one spring morning, he filled a woven bag with silvery fallen leaves. They didn’t make it into this exhibition, but they’ll likely show up in another. Adler likes the way they curl and how their veins protrude. Once a year or so, he travels to his native Missouri to gather horsetail rush, another favorite material.

“It’s the oldest plant known to man,” he says of the stalky reeds. “Dinosaurs ate it along with ferns.” The plant indeed dates back some 350 million years, according to several horticultural sites, and is sometimes called “a living fossil.” At home in Naples, he spreads them out by the bushel, and intermittently soaks and dehydrates them until they achieve the color variations he’s seeking. Then he manipulates them into natural sculptures.

A fellow artist, Marcela Pulgarin, and other assistants help him wrangle and hoist oversized pieces into place. Most of the creative process takes place on site. The Garden show, for example, is the first he’s hung from a ceiling, prompting the creation of two-sided works. Kapnick Hall’s skylights offer a bonus: a chance to spotlight certain pieces, as well as create dimension-adding shadows as the sun shifts.

Adler’s works are unnamed and without museum panels. “I like to look at art, other people’s and my own, without any preconceived notions,” he says.

He glances around Kapnick Hall again. Outside the picture window is the LaGrippe Orchid Garden, in Technicolor splendor. Beyond the doors are the Hoffmann Performance Lawn ringed with trees, the Water Garden bursting with waterlilies, the Lea Asian Garden in its shadowy mystique.

The hall is just as alive.

“I call this the garden, the secret garden within the Garden,” Adler says. “That’s how I refer to its mood.”

Internalizing the External: A New Perspective on Nature by Ran Adler (July 20 – October 27) is included with Garden admission, free for Members.

About the Author

Jennifer Reed is the Garden’s Editorial Director and a longtime Southwest Florida journalist.