With a few tweaks to your landscape, you can support a spectrum of insects, birds, and bats—and the plants that depend on them.

Search online for “butterfly gardens,” and you will find books, inspirational pictures, kits, how-to guides, nursery advertisements, demonstration landscapes, and endless other content. People sure do love lepidopterans!

We at the Garden, however, argue it’s time to start sharing our affection—and our landscapes. Certainly, butterflies are important pollinators. But so are bees, birds, bats, beetles, moths, flies, and the wind, all of which move pollen from plant to plant, triggering the production of fruit and seeds. Some 80% of the world’s flowering plants—including our fruits, vegetables, beans, and nuts—require pollination.

Pollinators are in peril because of habitat loss, pesticide use, increased temperatures, and dwindling plant diversity. While humans can grow new plants through cuttings of existing ones, that practice produces genetically identical plants. The loss of genetic diversity weakens plants and makes them more susceptible to disease. In short: Pollinators keep our ecosystems and crops healthy.

“We can’t conserve plants on our own in a lab,” says Vice President of Education & Interpretation Britt Patterson-Weber. “We need redundancy and diversity in our systems, just as a human would diversify their financial savings. Pollinators are doing this work for free.”

So, let’s remove our “butterfly blinders” and start thinking about planting for a spectrum of pollinators. With a few tweaks to your landscape, you can support many types of species moving pollen among many types of plants.

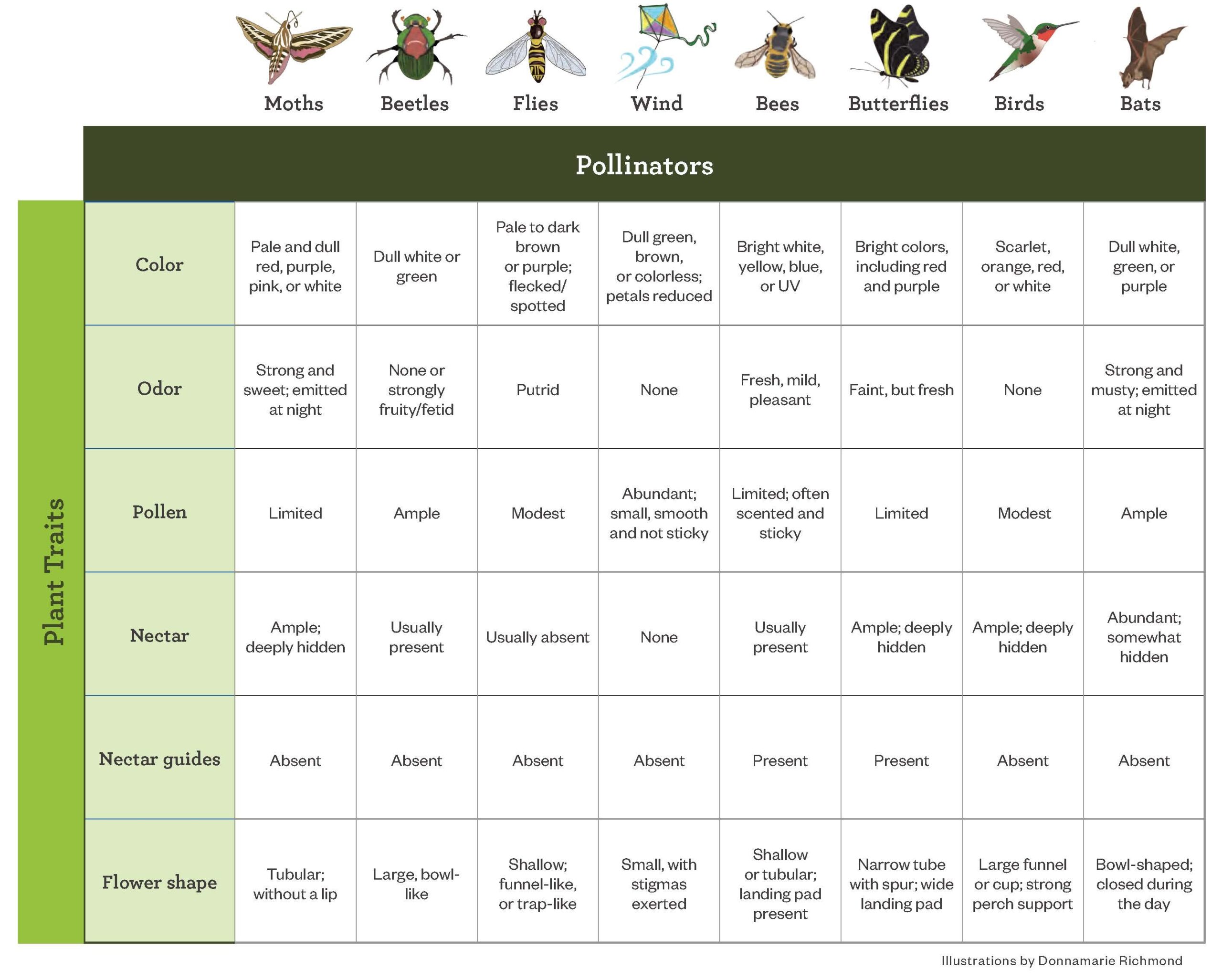

Save this chart for reference as you select plants for your pollinator-friendly landscape!

How pollination works

A flower’s anthers, its male component, produce dust-like pollen granules. This pollen must be deposited in the stigma, or female part of a flower, to trigger reproduction. It’s true that some plants can self-pollinate, but by and large, plants depend on helpers to spread their genetics.

Over the eons, plants and their pollinators have coevolved, developing physical characteristics that make them more likely to interact:

- Hummingbirds, for example, seek tubular flowers that complement their long beaks.

- Beetles, nature’s “recyclers,” gravitate to fetid-smelling plants.

- Nocturnal bats favor flowers that bloom or emit fragrance at night.

“Unlike animals, plants can’t travel around their habitats to seek the most attractive mate,” says Patterson-Weber, “Plants need an agent to transfer pollen for them. Isn’t it cool that a whole kingdom of non-sentient organisms has gotten animals to work for them?”

Pollinator-friendly yards

Here are several steps you can take to support pollinators:

- Avoid pesticides. These toxic compounds are among the biggest contributors to pollinator decline.

- Diversify your plants. See the chart below to understand how different flowering plants attract different pollinators. Research plant bloom times and select species that flower at different times of the year.

- Confirm your plant selections are not invasive. The Florida Natural Areas Inventory offers an invasive plant directory on its website.

- Don’t give up your annuals! Even as you create a more deliberate landscape, there is nothing wrong with a little eye candy. While annual ornamental plants can’t support complex pollinator communities on their own, they can meet the needs of generalist pollinators, those that are attracted to a range of plants.

- Incorporate showy native grasses into your landscape to add visual interest wild supporting wildlife. Grasses don’t require an animal pollinator (the wind spreads their genetics), but they do provide nesting material and wildlife habitat, and can feed some pollinators in their larval stage. Lopsided indiangrass (Sorghastrum secundum), for example, hosts three species of butterfly.

- Consider pollinators when designing potted plant arrangements. Even small steps like this make a difference.

Not sure where to start? The Institute for Regional Conservation’s “Natives for Your Neighborhood” database allows South Florida residents to search native plants by ZIP code to identify the trees, shrubs, grasses, groundcovers, vines, and wildflowers best suited for their region.

The unusual suspects

- We wouldn’t have chocolate if not for no-see-ums. They may be the bane of our existence, but the teeny-tiny bugs are just the right size to pollinate miniscule cacao tree flowers, which are smaller than a thumbnail.

- We don’t usually think of snails as pollinators, but they pollinate roundleaf bindweed (Evolvulus nummularius), an annual herb in the morning glory family. We imagine the process is slow.

- Some plant species can “hear” their pollinators through sound waves and ramp up nectar production within minutes, a phenomenon called “phytoacoustics.” A good example is beach evening primrose (Oenothera drummondii), which increased its sugar production by 12 to 20% when exposed to a bee’s hum, as demonstrated in a 2019 study by an evolutionary theoretician at Tel Aviv University.

- Conversely, the Evolvulus evenia, a rainforest vine native to Cuba, produces a cup-shaped leaf above its flower. Its pollinators, nectar-feeding bats, find the flower by bouncing sound off the leaf’s surface.

Did you ever consider how a carnivorous plant can achieve pollination without eating its reproductive helper?

They have a few strategies:

- Their flowers are usually high above the ground and attract flying pollinators, while their traps are situated lower and swallow non-flying prey.

- They reproduce first and eat later by developing flowers to attract pollinators and then traps to lure prey once the flowers fall away.

- They produce pollinator-attracting fragrances in their flowers and scents or color patterns that draw food in their traps.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2024 issue of Cultivate, the Garden’s magazine.